Yes, Ahmed Best needed redemption

Redemptive moments are not just for evil doers

Jar Jar Binks does not have a good reputation. For the two decades since the release of Star Wars: Episode I: The Phantom Menace, conversation amongst fans about the kickoff to George Lucas’ prequel trilogy inevitably involves someone in that dialogue citing the gangly Gungan in their case against Episode I. If only we could all get a dollar for every time the banal “But Jar Jar, am I right?” was deployed within fandom debate to substitute for an original thought.

Regardless, Binks hangs over the Star Wars prequel’s legacy like a cloud. Just ask Ahmed Best, the actor who brought the CGI amalgamation to life. Jar Jar nearly killed Best, or more so, his association with Star Wars and its rancorous fans did. The young actor contemplated and took literal steps toward suicide on the Brooklyn Bridge in the years following The Phantom Menace, exhausted and demoralized by the venom directed both at him and his work.

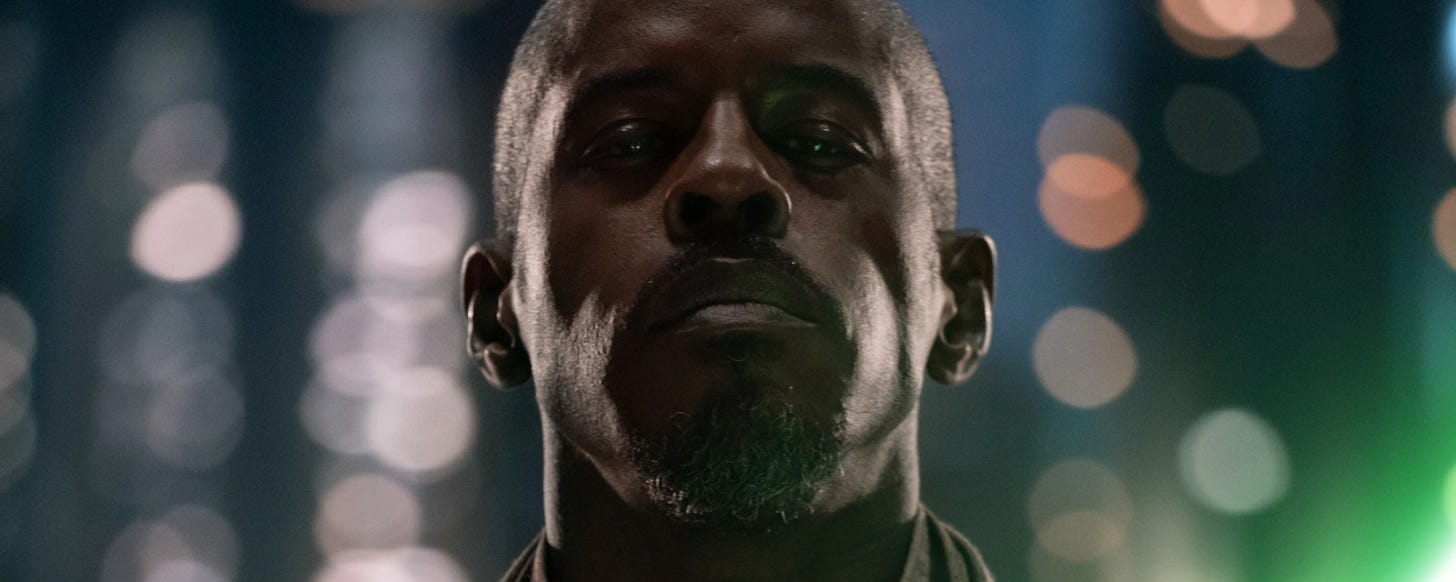

He didn’t do anything wrong, but Ahmed Best has suffered nevertheless. Fast forward to today and in Chapter 20 of The Mandalorian, it was finally answered how Grogu (Baby Yoda) survived the Jedi purge of Order 66. A Jedi Master named Kelleran Beq, played by none other than Ahmed Best, rescued Grogu from Clone Troopers and shuttled him to a starship to escape the massacre. It was a very cool sequence. Best duel-wielded lightsabers battled it out with numerous Clones and even led a speeder chase through the above-ground tunnels of Coruscant.

Ahmed Best returned to the world of Star Wars in the most popular installment to the franchise since the Disney era began in 2015, The Mandalorian. It’s true he’s been in LucasFilm’s orbit for a few years, first as the Jedi and host of a Star Wars-themed game show on Disney+, but The Mandalorian is what you might call prime-time in the world of streaming.

As far as the definition of redemptive stories goes, this one fits the bill. But don’t tell that to Star Wars fans out to champion Ahmed Best in this moment of triumph. When Rolling Stone used the words “redemption arc” to describe the Jar Jar Binks actor's role in The Mandalorian, it set off a rhetorical debate that illustrates very clearly why our society struggles with redemption narratives.

In The Digital Fix, Charlotte Colombo drove home the disconnect in saying “By definition, ‘redemption’ refers to “atoning for a fault or mistake,” so to say Best is being given a shot at ‘redemption’ is to say that he is to blame for the backlash surrounding Jar Jar. And if that’s the implication, then that leads us to the worrying conclusion that Best somehow deserved all the abuse he received.”

Colombo accurately hits on one of many meanings of redemption.

You only end up here by having a wholly secular and contemporary understanding of what redemption means. It’s not anyone's fault. The common use of the word “redemption” as well as phrases like “redemption arc” immediately invoke wicked characters turning a new leaf and trying to right their wrongs. Darth Vader casts the Emperor into an abyss and saves his son, Luke Skywalker. Kylo Ren faces a vision of his murdered father, Han Solo, and chooses to cast his red lightsaber into the sea. He relinquishes the dark side and returns “home” to his true identity as Ben Solo. Of course, nothing really gets set right. Both characters help defeat the arch-villain and die in the process. Their debts to the galaxy, ones of countless evils, are not even close to reconciled.

The thing about redemption tales is that they’re not really fair. In the Judeo-Christian construct on which most of the Western canon is built, redemption refers not only to atoning for a fault, but also to the payment of a debt, the buying of one’s freedom out of slavery, and the deliverance of a people from evil. The act of redeeming yourself, an experience or a reputation, has nothing at all to do with your faults. It’s about your ability to turn shit into gold, to find beauty in negative spaces, and to see the good within hurt.

Ahmed Best did nothing wrong, but his life was nearly destroyed by working on Star Wars. The fans and the critics who couldn’t find it within their intellect to segment feelings about Jar Jar Binks from the film itself did Ahmed Best (and Jake Lloyd) wrong.

There will be no apology. Who would deliver it? Who is in a position to apologize on behalf of “the fans” to Ahmed Best? No one, of course. The pain Best experienced was inflicted by an amorphous collective with no face or name. “The fans” aren’t a real thing and changes constantly. Consider Hayden Christensen’s return to the world of Star Wars after his also maligned performance as the older Anakin Skywalker of Episodes II and III. Fans chanted his name in a standing ovation at Star Wars Celebration in 2017 and again in 2022. You could call that an “apology” of sorts being given by a mostly new generation of Star Wars fans steeped in prequel nostalgia, but the perpetrators of past wrongs were very likely not in those crowds.

If you go down the road of an apology being required for an actor who experienced the rejection and shame associated with involvement in the Star Wars prequels, you give the fans all the power. This is wrong. Redemption is about reclaiming power, rebuilding hope, and restoring beauty in an otherwise broken life.

Redemption is not about getting permission or being given your due. It can be about that. When the father of a murdered daughter gave forgiveness to his child's killer in CNN’s The Redemption Project, that act of incredible grace gives the victimizer an opportunity to move forward in their journey. Redemption is found in the mirror when a person can look at themself and know in their heart that they are not the person they were yesterday. Sometimes that means you’re the villain trying to be the good guy for a change, and sometimes it means you’re the victim of that same villain’s transgressions, once broken but now back on your feet.

Ahmed Best was once suicidal and stripped clean of his self-worth and hope for life. Redemption for Ahmed was in fact needed. For that to happen, he needed not just an opportunity but the courage to walk back through the same door that hurt him so badly…Star Wars.

“20 years later I’m on the bridge with my son and I’m looking at the spot-” the beam of the Brooklyn Bridge from where Best nearly took his own life. He took a picture there with an arm around his young son and posted it online. This spot on the bridge was now more than it was before. The Brooklyn Bridge was a place of pain for Ahmed Best once, clouded in a “fog” that as Best described, prevented him from seeing the beauty and promise of New York City’s lights. Now this place was something more.

The bridge didn’t do anything wrong. It’s just a location. But even a bridge can be redeemed in your heart when it comes to symbolizing renewal instead of death and despair.

Ahmed Best is now more than Jar Jar Binks when it comes to Star Wars. He’s also a Jedi Master named Kelleran Beq. He saved Grogu, perhaps the most beloved intergenerational character in Star Wars of recent memory, from death in the Jedi Temple. Best did nothing wrong. Star Wars wronged him. But in 2023 he was still alive to let Star Wars’ showrunners open the door for him to a new chapter and brighter memory.

Cheers to Ahmed Best’s redemption arc within Star Wars. The best is always yet to come.

This is the way

Stephen Kent is the author of How The Force Can Fix The World: Lessons on Life, Liberty, and Happiness from a Galaxy Far, Far Away, a book about the political virtues of the Star Wars saga.

How Ahmed Best, Jake Lloyd, and Hayden Christensen were all treated always appalled me. I didn’t like their characters or think much of their acting, but so what? And ‘fans’ haven’t learned at all, because they did the same thing to Kelly Marie Tran, the first young Asian woman I had seen in a mainstream film who wasn’t sexualised, a baddie, and/ or victimised to make space for a white hero.