The Mandalorian in an age of estrangement

We’ve raised a generation of mercenaries and bounty hunters

Loneliness has become a real problem. So much so that the United States Surgeon General is doing a full-court press to speak about its detrimental effects on the individual and the larger society. Isolation from others comes with all manner of downstream ills: increased risk of heart disease, dementia, stroke, and of course, depression, and suicide. We all have something top of mind that we blame for this. Technology. The pandemic. Hatred. Entertainment. You name it. Regardless of what is to blame, this is an actual crisis. Not one of the made-up ones you hear about on TV each night. American hospital beds are being crowded out by a generation of children expressing suicidal ideation, severe depression, and loneliness. The situation is not much better for our friends over the age of 50. Their communities and social capital has been flattened in the last quarter century as well.

What are we going to do?

I am not a “joiner”

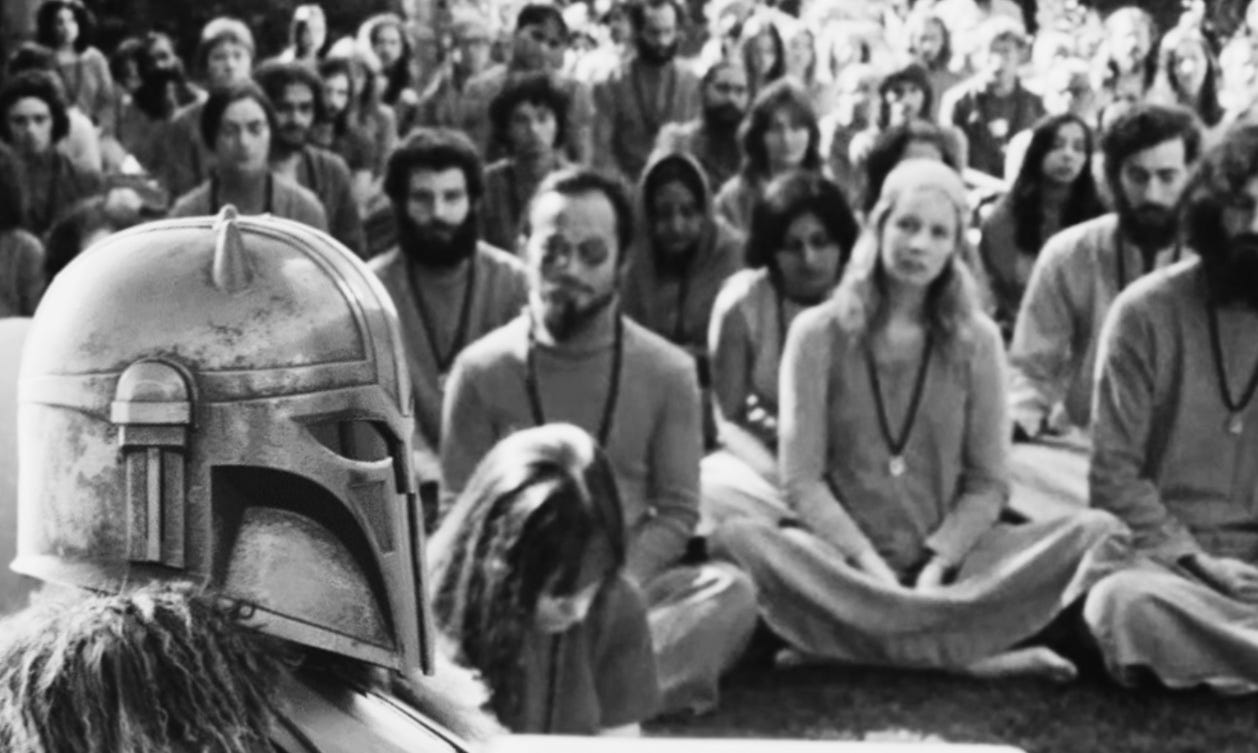

Tomorrow is May 4th, and Star Wars fans (me included) are going to be shouting #MayThe4thBeWithYou endlessly for the next 48 hours. I’ve always felt somewhat lonely in my life. My personality is that of a person who says, “I’m not a joiner.” I go to church, but I resist connection. I am involved in politics, but I refuse to drink the partisan Kool-Aid. I have a few friends, but I don’t know how to turn casual friendships into deep ones. My guard has always been up, and it will be a lifelong struggle to lower it. But still, if I ever have had “a community” it’s been the Star Wars fans of the world. We talk online, form chat groups, go to events together, and sometimes become real-world friends. Star Wars is very meaningful to me. And so as I watched the latest season of The Mandalorian and Bo-Katan’s visible struggle with loneliness, I deeply felt the show’s relevance to our time and place in history. In this short essay, I’ll explain.

The Mandalorian in an age of estrangement

“They’re a cult” sneers Bo-Katan Kryze to Din Djarin, otherwise known to audiences as “The Mandalorian” for whom the Star Wars series on Disney+ is named. Bo-Katan, the aspiring ruler of a hollowed out world called Mandalore, has nothing nice to say about the Children of the Watch, a Mandalorian splinter group which Din Djarin has been a part of since being orphaned as a child. She is on a Game of Thrones-esque quest to lead Mandalore into a new age, but the once dismissive Bo-Katan had yet to careen over the cliff of her ambition.

In the start of the most recent third season of The Mandalorian, Bo-Katan is alone, rudderless and out of options. We find her secluded in the halls of her family castle, abandoned by fairweather supporters and realizing for the first time in her individualistic existence that the strange “zealots” of the Watch have something she does not: A sense of what it means to be “a Mandalorian”.

You’ve likely seen in the news by now the much discussed Wall Street Journal–NORC poll that shows radical declines in Americans' relationship to the values of patriotism, religion, family and community service.

The stated value of religiosity to respondents has plunged from 62% to 39% since 1998. Community involvement went from 47% to 27%. Having children, the literal act of expanding one’s heritage, dropped 29 points to 30%. Tolerance as a virtue dove from 80% to 58%. You’d expect the opposite from a culture where elites primarily espouse diversity and inclusion as being amongst their bedrock principles.

It is all quite shocking. The only item on the list to increase its standing in the American psyche was the importance of money, which rose from 31% to 43%.

It seems we’ve raised an American generation of bounty hunters and mercenaries.

The Mandalorians were once a warrior culture with a homeworld and military might. Decades of civil strife and eventually a purge by the Empire left them with nothing save a few cave hideouts and opportunities to freelance their art of war. That’s why we see so many Mandalorians throughout Star Wars lore in the role of rogueish gun-for-hire.

I’ll spare you a Mandalorian history lesson, but the long story short is that their internal differences during The Mandalorian TV series boil down to whether or not being a Mandalorian is about a creed and way of life (This Is The Way) or if its about blood and soil.

These are subtleties to Disney’s The Mandalorian that don’t go unnoticed by Star Wars fans and even some casual observers. Like with a good deal of Star Wars’ political worldbuilding, its relevance to the real world is more often than not, coincidental. We can argue all day about Ewoks and Vietnam allegories for the original trilogy, but unless George Lucas “did 9/11” there’s no way he could have outlined his prequel trilogy of Star Wars Episodes’ I-III with knowledge of what was to come in America during the Bush years.

But some things are universal and to be expected in the course of history, such as the clash between safety and liberty that those early aughts films captured. The Mandalorian is similarly positioned to speak to its fans in the West about this “Tower of Babble moment” of uncertainty about who we are, where we come from, where we’re going and why.

Everything looks like a cult to the loner with no ties or obligation to others.

Bo-Katan is asking these questions when we find her slouched in misery on her family throne. She was traveling with two like minded warriors, Axe Wolves and Koska Reeves, to put together a fighting force for the retaking of Mandalore. That was contingent upon her possessing the Dark Saber, an artifact of Mandalorian life that now belongs by rite to Din Djarin. It was acquired when he defeated a rogue Imperial warlord, Moff Gideon, in single combat. For Bo-Katan to take it, she’d have to fight “The Mandalorian”, which both parties appear unwilling to do.

So she’s left with nothing and nobody. No homeland, no community, no family.

I couldn’t help but laugh at Bo-Katan’s struggle here. Perhaps she’d like to be part of “a cult” now. It’s not perfect but it’s certainly better than whatever she was doing.

And that’s exactly what happened next. Bo-Katan helmets up and joins the Children of the Watch.

The rules of the Way

Members of the Watch subscribe to more ancient dogmas about the way a Mandalorian is meant to live. Above all else, they do not remove their helmets in the presence of others, ever. It is forbidden and an offense worthy of exile from the group. “This Is The Way'', that slogan you now see all over minivan bumper stickers, is their motto. It’s a powerful summation of the Children of the Watch’s call to walk in tradition, stomach rules, meet expectations and expand the creed.

That last part is crucial. To walk “The Way” is not just to wear your helmet, obscuring your individual identity, it is also to adopt foundlings into their way of life. That is the only way in which a tiny creature like Baby Yoda (AKA The Child AKA Grogu) could credibly hang out with Mandalorians and be considered an equal. Tolerance is foundational to the Watch. After all, everyone is the same once the armor is forged and helmet goes on. The same can’t be said for Bo-Katan’s old crew, who have repeatedly tried to play gatekeeper on who can be Mandalorian and who cannot.

“The cult” is actually open than the Mandalorians by way of blood. They honorhaving children and welcoming outsiders who are willing to live within the culture. It’s foundational to what This Is The Way is all about. And it gives them reason for being.

Think about it. The Mandalorian series begins with Din Djarin living in association with the Watch, but he’s working full-time as a bounty hunter for hire. The man sounds visibly exhausted every time he finds his target and offers “bring you in hot, or bring you in cold.” It’s only when Din Djarin finds Grogu and takes the creature on as his charge, does he unlock a motivation and purpose for his life.

Grogu becoming a foundling brings The Mandalorian closer to his kin and begins his own hero's journey.

There are worse things than having people

Maybe the Children of the Watch are a cult. There’s not a universally accepted set of markers that separates a cult from a mainstream religious organization or even a secular club. I go to church and kneel before a wooden cross with a hundred other people around me, strange to nonbelievers I’ve heard. I also have been in Boy Scouts since I was 12, once as a “foundling” if you will, and now as an Eagle Scout and Scoutmaster. I guess my daughter is a foundling now too, as we stand together in matching outfits weekly to recite a Law and Code calling us to “do our duty to God and Country” and to remain “physically strong, mentally awake and morally straight.”

Everything looks like a cult to the loner with no ties or obligation to others.

But we do know that cults have rigid dogmas, are closed off from the rest of the world, and center around enigmatic leaders who often supersede those dogmas and live beyond their strictures. The leader is the law. Thus the rules of the group are flexible for them and them alone. Typically, the laws of the outside world are also held in contempt, which is why cult leaders have a knack for ending up on true crime Netflix playlists.

Something our Mandalorian friend Din Djarin would recognize about cults is that members can be rapidly canceled and made apostates. They get smeared, defamed and rendered untouchable if they step outside the pieties of the group. He was made an apostate once for removing his helmet (several times) in service of Baby Yoda. So he was dismissed, except not really.

The leader of the Children of the Watch, known only as The Armorer, oversaw Din Djarin’s exclusion from the group, but his expulsion from The Way wasn’t final in the slightest. He has a pathway to redemption offered in very clear terms. Travel to Mandalore and bathe in the “living waters” beneath the surface of the planet, and his transgressions against the community would be wiped away. The Armorer does not break rules to her benefit, nor does she defy the codes of the conduct she enforces on members. Mandalorians who walk The Way may come and go freely as they choose.

We should all recognize what Bo-Katan came to see, which is that the Children of the Watch are not a cult, and even if they were, there are worse things than joining.

America’s cultural and spiritual malaise has been a long time coming. There are numerous places online you can go to get finger-pointing for who caused it and what solutions there might be. That’s not the point here. Whatever forces pushed us to this moment where hospital beds are being crowded out by children expressing suicidal ideation and where 1,019 Americans surveyed by NORC appear totally unmoored from societal obligation, we can still grab hold of stories that move us.

There’s an interesting line from The Mandalorian’s titular villain, Moff Gideon, where he says about the highly coveted Dark Saber which Bo-Katan seeks, “The Darksaber,” he says, “doesn’t have power; the story does,”

The Mandalorian, just like Star Wars’ Skywalker tale that began in 1977, is one of those stories that has a unique power to speak to its fans through the fog of disillusionment. We should all be listening.

This is the Way.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this essay and want to get connected to our little community here on Substack, please Subscribe and consider becoming a Paid supporter.

A fun new project is on the horizon to expand This Is The Way. Stay tuned for more information.