Hope in the Soil

Exploring Tolkien’s Environmentalism

A major reason why J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings has resonated with audiences of all ages since publication is because of its ability to re-enchant the soul with the good, true, and beautiful in the midst of an increasingly brazen and militant evil. It is a great romance (like the legendary medieval texts that inspired Tolkien) that doesn’t shy away from the reality of dragons prowling at your doorstep. As Bilbo tells Frodo about the “dangerous business” of leaving home, we can hear Tolkien echoing that same counsel to his audience. And yet, far from turning to a cynical view of reality, at the core of this beloved trilogy is the recovery of hope.

Of all the visceral images in The Lord of the Rings, the one that resonates with me the most is when Frodo and Sam have descended entirely into the land of shadow, devoid of the most basic necessities, as they make their way to Mount Doom to complete their quest of destroying the One Ring. In his films, Peter Jackson did an excellent job of visualizing just how excruciating and laborious this last stretch of the hobbits’ journey was. And of course, the iconic image of Sam carrying a beleaguered and destitute Frodo up the foothills of Mount Doom draws a tear from even the hardiest of hardy men.

Now, although the movie did an excellent job with this sequence, there was one scene from the books that I wish had been included. It is one of those scenes that is easy to overlook on a first or second read, but when you finally notice it, you will find a tremendous amount of depth.

During Frodo and Sam’s harrowing trek, as the shadow increased and “light grew no stronger,” the hobbits were met with an unexpected gift.

They had trudged for more than an hour when they heard a sound that brought them to a halt. Unbelievable, but unmistakable. Water trickling. Out of a gully on the left, so sharp and narrow that it looked as if the black cliff had been cloven by some huge axe, water came dripping down: the last remains, maybe of some sweet rain gathered from sunlit seas, but ill-fated to fall at last upon the walls of the Black Land and wander fruitless down into the dust. Here it came out of the rock in a little falling stremlet, and flowed across the path, and turning south ran away swiftly to be lost among the dead stones.

Throughout their journey, Frodo and Sam are regularly sustained by the gifts of others. Galadriel gives Frodo a phial of starlight from the great elf-turned-star, Eärendil, that comes in clutch in Shelob’s lair. Faramir, the young captain of Gondor, gives them provisions and wise counsel about the road ahead. Lastly, the lembas bread, provided by the elves of Lothlorien, played such a large role in nourishing them along their way.

And now, at this point, when they are waterless and weary, they receive another needed gift. But this time it doesn’t come from the hand of a creature of light (at least not directly). The gift this time around is trickling out of the earth. This water, far from being arbitrary and insignificant, is a vestige of an all but forgotten age when Mordor wasn’t a desolate wasteland. In a way, it is a microscopic picture of the shadow being quenched.

But we must go further. To understand this, we need to understand Tolkien himself. Specifically, we need to understand his environmental philosophy.

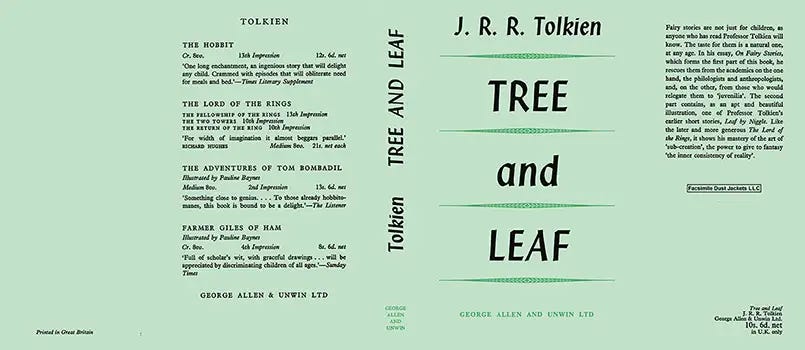

To put it mildly, he was a bit of a tree-hugger. He cared significantly about the natural world. Indeed, one of the primary inspirations for the writing of his allegorical, autobiographical short story, “Leaf by Niggle,” was witnessing his neighbor cutting down a tree he enjoyed looking at. He writes:

One of its [“Leaf by Niggle”] sources was a great-limbed poplar tree that I could see even lying in bed. It was suddenly lopped and mutilated by its owner, I do not know why. It is cut down now, a less barbarous punishment for any crimes it may have been accused of, such as being large and alive. I do not think it had any friends, or any mourners, except myself and a pair of owls.

In regards to Middle-Earth, Tolkien’s environmentalism is all over the place, but is probably best expressed by the Ents, the shepherds of the forest, caring and tending for the rest of the wood.

At the heart of Tolkien’s view is the necessity of stewardship. As a Christian, Tolkien wholeheartedly believed in the dominion of man over creation and his responsibility to subdue and care for creation.

And if man neglects this responsibility, or even worse, works against that end—chaos and disorder emerge on every level.

What can’t be ignored here: there is an inextricable link between the spiritual and the physical.

That is what is happening in places like Mordor and Isengard. Instead of properly-ordered dominion and stewardship taking place, Sauron (and Saruman after him) are dominating nature. They are ravaging and destroying nature to serve their own interests.

Returning to the trickling water in Mordor, that is why it is so “unbelievable” that a land so ravaged and torn by evil can still have this small ray of hope. It conveys more than momentary respite for the hobbits; it shows that things can be restored, no matter how broken it has become.

Hope isn’t just the ethereal, or a mindset; it is, quite literally, embedded in the soil, in creation. And no matter how much evil and disorder work to dominate the good, it can never fully stamp out what the Creator purposed His creation to be.

Thanks for reading Geeky Stoics!

We are a community of fantasy, sci-fi, and fiction nerds with a passion for timeless philosophy. On Substack and YouTube, we tackle stoicism, apologetics, faith, and much more through the lens of Star Wars, LOTR, Narnia, Harry Potter, and other classics.

We hope you’ll subscribe and become part of the Geeky Stoics family.

For more on Tolkien’s philosophy, check out these from Geeky Stoics