America is dying from a lack of mythology

Just this week get 40% off annual subscriptions

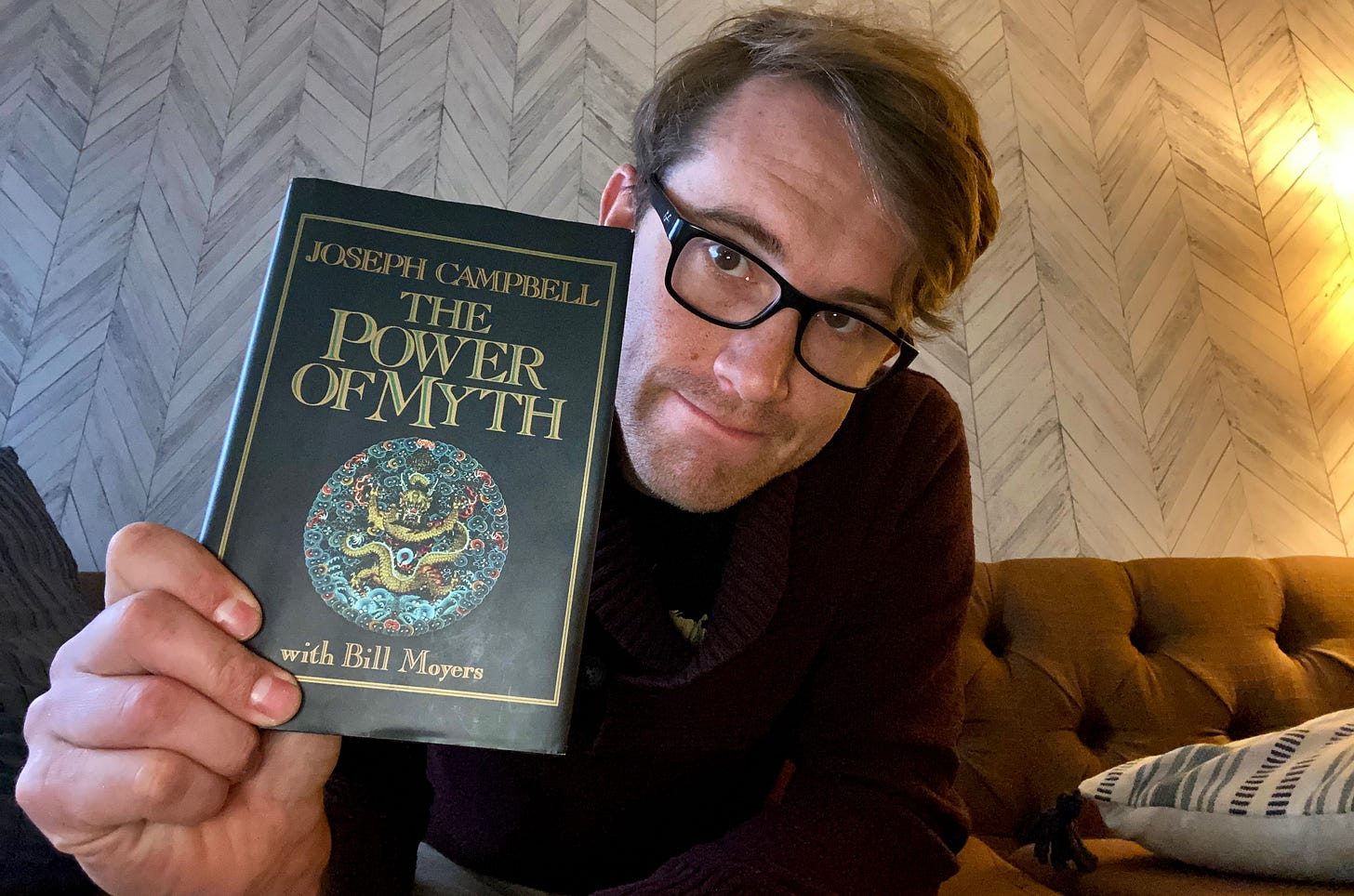

Today I’m excited to preview a little something I’ve been working on for This Is The Way. It’s a dramatized reading of a dialogue between Joseph Campbell and journalist Bill Moyers, captured in The Power of Myth. I’m loving this book, and even though it is from 1988 it feels like it was meant for today. In this clip, Campbell is narrated by my dear friend, William Walker Smith, and I voice Moyers. They’re discussing crime in America as a consequence of mythology’s decline in the West. Stories we tell ourselves about Coming of Age and societal responsibility have always mattered to every civilization that has walked this Earth, except for here and now.

This is the audio version of that performance by Will and myself. A video version is in production, with numerous segments from the book being read for Paid Supporters of This Is The Way.

But first, a 40% off discount worth taking

We are marking down Annual packages for Paid Access to This Is The Way. Normally $50, it’s 40% off for the next week at only $30.

After this week, specialized content like this will be behind the paywall. It takes A LOT of work to produce between the reading, research, rewriting, recording, and then video production. Join the fun by becoming a Paid Subscriber. Now…enjoy this installment of The Power of Myth.

Transcript for this section:

The Power of Myth, a conversation between Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers, was captured on Skywalker Ranch for TV and was later published in book form.

MOYERS: What happens when a society no longer embraces a powerful mythology?

CAMPBELL: What we've got on our hands. If you want to find out what it means to have a society without any rituals, read the New York Times.

MOYERS: And you'd find?

CAMPBELL: The news of the day, including destructive and violent acts by young people who don't know how to behave in a civilized society.

MOYERS: Society has provided them no rituals by which they become members of the tribe, of the community. All children need to be twice born, to learn to function rationally in the present world, leaving childhood behind. I think of that passage in the first book of Corinthians: "When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things."

CAMPBELL: That's exactly it. That's the significance of the puberty rites. In primal societies, there are teeth knocked out, there are scarifications, there are circumcisions, there are all kinds of things done. So you don't have your little baby body anymore, you're something else entirely.

When I was a kid, we wore short trousers, you know, knee pants. And then there was a great moment when you put on long pants. Boys now don't get that. I see even five-year olds walking around with long trousers. When are they going to know that they're now men and must put aside childish things?

MOYERS: Where do the kids growing up in the city -- on 125th and Broadway, for example -- where do these kids get their myths today?

CAMPBELL: They make them up themselves. This is why we have graffiti all over the city. These kids have their own gangs and their own initiations and their own morality, and they're doing the best they can. But they're dangerous because their own laws are not those of the city. They have not been initiated into our society.

MOYERS: Rollo May says there is so much violence in American society today because there are no more great myths to help young men and women relate to the world or to understand that world beyond what is seen.

CAMPBELL: Yes, but another reason for the high level of violence here is that America

has no ethos.

MOYERS: Explain.

CAMPBELL: In American football, for example, the rules are very strict and complex. If you were to go to England, however, you would find that the rugby rules are not that strict. When I was a student back in the twenties, there were a couple of young men who constituted a marvelous forward-passing pair. They went to Oxford on scholarship and

joined the rugby team and one day they introduced the forward pass. And the English players said, "Well, we have no rules for this, so please don't. We don't play that way."

Now, in a culture that has been homogeneous for some time, there are a number of understood, unwritten rules by which people live. There is an ethos there, there is a mode, an understanding that, "we don't do it that way."

MOYERS: A mythology.

CAMPBELL: An unstated mythology, you might say. This is the way we use a fork and knife, this is the way we deal with people, and so forth. It's not all written down in books. But in America we have people from all kinds of backgrounds, all in a cluster, together, and consequently law has become very important in this country. Lawyers and law are what hold us together. There is no ethos. Do you see what I mean?

MOYERS: Yes. It's what De Tocqueville described when he first arrived here a hundred and sixty years ago to discover "a tumult of anarchy."

CAMPBELL: What we have today is a demythologized world. And, as a result, the students I meet are very much interested in mythology because myths bring them messages. Now, I can't tell you what the messages are that the study of mythology is bringing to young people today. I know what it did for me. But it is doing something for them. When I go to lecture at any college, the room is bursting with students who have come to hear what I have to say. The faculty very often assigns me to a room that's a little small -- smaller than it should have been because they didn't know how much excitement there was going to be in the student body.

MOYERS: Take a guess. What do you think the mythology, the stories they're going to hear from you, do for them?

CAMPBELL: They're stories about the wisdom of life, they really are. What we're learning in our schools is not the wisdom of life. We're learning technologies, we're getting information. There's a curious reluctance on the part of faculties to indicate the life values of their subjects. In our sciences today -- and this includes anthropology, linguistics, the study of religions, and so forth -- there is a tendency to specialization. And when you know how much a specialist scholar has to know in order to be a competent specialist, you can understand this tendency. To study Buddhism, for instance, you have to be able to handle not only all the European languages in which the

discussions of the Oriental come, particularly French, German, English, and Italian, but also Sanskrit, Chinese, Japanese, Tibetan, and several other languages. Now, this is a tremendous task. Such a specialist can't also be wondering about the difference between the Iroquois and Algonquin.

Specialization tends to limit the field of problems that the specialist is concerned with. Now, the person who isn't a specialist, but a generalist like myself, sees something over here that he has learned from one specialist, something over there that he has learned from another specialist -- and neither of them has considered the problem of why this

occurs here and also there. So the generalist -- and that's a derogatory term, by the way, for academics -- gets into a range of other problems that are more genuinely human, you might say, than specifically cultural.

MOYERS: Then along comes the journalist who has a license to explain things he doesn't understand.

New on our YouTube today

A video take on a recent post from This Is The Way. Support us by Subscribing to the YouTube channel.